The Times They Are A-Changing… Being the Church in a Secular, Liberal, Pluralist Democracy

Friday, 18 September 2015

| Scott Higgins

The centuries from the Enlightenment until the present have seen the decline of Christendom and the rise of liberal, secular, pluralist democracies. They are “liberal” in that individuals possess rights that their fellow citizens and the state are obligated to respect; “secular” in that no religion is preferred by government nor is legislation formed on the basis of religious views; and “pluralist” in that citizens, organisations, and social institutions are free to pursue their own interests and values. This has dramatically reshaped the place of the church in society and societal expectations around virtue.

James Davison Hunter notes that

pluralism in its most basic expression is nothing more than a simultaneous presence of multiple cultures and those who inhabit those cultures… In most times and places in human history, pluralism was the exception to the rule; where it existed, it operated within the framework of a strong dominant culture. If one were part of a minority community, one understood the governing assumptions, conventions, and practices of social life and learned how to operate within them.… But pluralism today – at least in America – exists without a dominant culture, at least not one of overwhelming credibility or one that is beyond challenge… For the foreseeable future, the likelihood that any one culture could become dominant in the way that Protestantism in Christianity did in the past is not great.

– To Change the World: The Irony, Tragedy, and Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World (Oxford University Press, 2010).

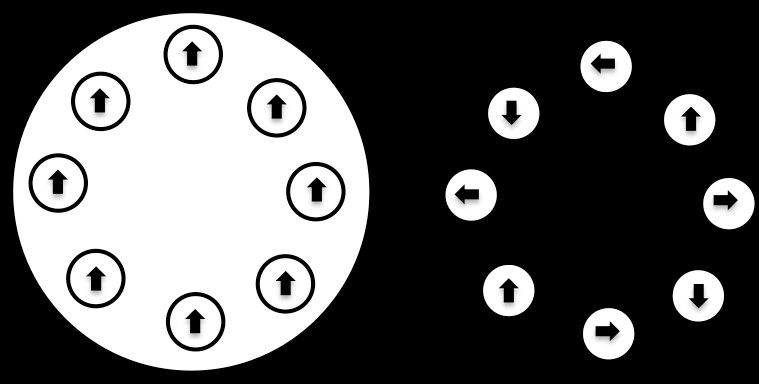

The shift to pluralism is represented in the diagram below.

The small circles represent the citizens that make up a community. In a homogenous society there is a dominant culture, represented in the diagram on the left by the thick circle that surrounds the smaller circles. It is the role of social institutions such as churches, schools, and government to embody the values of the dominant culture and to ensure people do not stray outside its boundaries. In a pluralist society the strong boundaries have evaporated, members of the society have different value sets and interests (represented by the arrows inside the circles) and the role of social institutions is not to keep people within particular cultural boundaries, but to facilitate the possibility for members of society to live their own values and interests. This can be a disorienting situation. We want to find the cultural centre, but there is not one.

In a pluralist democracy the role of government is not to dictate values and behaviours, but to coordinate society such that: 1) the various actors are free to determine their own values and pursue their own interests without infringing upon the freedoms of others; 2) the various actors in society can work cooperatively towards a common good.

Hunter identifies four possible responses to this new state of affairs. First, those who see pluralism as a threat and seek to make the culture Christian once more. Second, those who seek to make the church relevant to the concerns of contemporary pluralistic culture, more often than not by getting involved in social justice issues. Third, those who seek to withdraw into an ideal/pure community. Fourth, his own prescription, which he refers to as “faithful presence”, by which he means a commitment to the biblical vision of shalom that is enacted by being fully present to God, to others, to our tasks (in which we join with others in our culture in fulfilling the creation mandate to be world-making), and to our spheres of influence.

Though there is no biblically mandated form of government, a Christian response to Australia’s polity is well accommodated by Baptist theologies of church and state. In a Baptist understanding, the conscience can be governed by no one but God. This limits the role of the state, for it should never seek to command conscience, that is, the religious beliefs and values of its citizens, but has a far more limited role of maintaining public order so that citizens can live by the dictates of their conscience.

Consistent with this, the reformed understanding in the Kuyperian tradition argues that within any society there are multiple spheres of responsibility, including the individual, the household, social institutions, and government. These are each accountable to God for their behaviours and values, and neither the state nor the church should position themselves as the representatives of God to whom others must answer.

In light of this Miroslav Volf’s reflections on engagement in the public sphere in a pluralist society are helpful.

- 1. Christ is God’s word and God’s lamb, come into the world for the good of all people, who are all God’s creatures and loved by God. Christian faith is therefore a “prophetic” faith that seeks to mend the world. An idle or redundant faith – a faith that does not seek to mend the world – is a seriously malfunctioning faith. Faith should be active in all spheres of life: education and arts, business and politics, communication and entertainment, and more.

- Christ came to redeem the world by preaching, actively helping people, and dying a criminal’s death on behalf of the ungodly. In all aspects of his work, he was a bringer of grace. A coercive faith – a faith that seeks to impose itself and its wildlife on others through any form of coercion – is also seriously malfunctioning faith.

- When it comes to life in the world, to follow Christ means to care for others (as well as for oneself) and work toward their flourishing, so that life should go well for all and that all would learn how to lead their lives well. A vision of human flourishing and the common good is the main thing the Christian faith brings into the public debate.

- Since the world is God’s creation and since the Word came to his own even if his own do not accept him (John 1:1), the proper stance of Christians toward the larger culture cannot that be that of unmitigated opposition or whole-scale transformation. A much more complex attitude is required – that of accepting, rejecting, learning from, transforming and subverting or putting to better uses various elements of an internally differentiated and rapidly changing culture.

- Jesus Christ is described in the New Testament as a “faithful witness” (Rev 1:5) and his followers understood themselves as witnesses (e.g. Acts 5: 32). The way Christians work toward human flourishing is not by imposing on others their vision of human flourishing and the common good but by bearing witness to Christ, who embodies the good life.

- Christ has not come with a blueprint for political arrangements; many kinds of political arrangements are compatible with the Christian faith, from monarchy to democracy. But in a pluralistic context, Christ’s command “in everything do to others as you would have them do to you” (Matt 7:12) entails that Christians grant to other religious communities the same religious and political freedoms that they claim for themselves. Put differently, Christians, even those who in their own religious views are exclusivists, ought to embrace pluralism as a political project

- A Public Faith: How Followers of Christ Should Serve the Common Good (Brazos Press, 2011)

Points 1 rules out withdrawal from the public space, points 2, 4, 5 and 6 rule out the attempt to coerce Christian values through legislation (i.e. the re-Christianising project), while points 3 and 4 point us in the direction of Hunter’s concept of “faithful presence”.

What the Church Can Expect from the State

In a liberal, secular, pluralist democracy the state should ensure freedom of religion, that is, it should ensure that every religious group and their members are free to believe and practice their faith. To be a secular society does not mean the state makes no place for religion, but that it does not preference one religion over another or religion over no religion. In a healthy liberal, secular, pluralist society we would expect to see many expressions of religious faith.

The corollary of this, is that the church should not expect the state to discriminate favourably towards it or unfavourably against it.

What the State Can Expect From the Church

The church is called to seek the flourishing of its community and does so on the understanding that the values of God’s kingdom represent the best way for humankind to flourish. In a secular, liberal, plural democracy this leaves the church with two instruments for engaging in the public space. First, the church has its public witness, in which by its words and deeds it encourages people toward the values of the kingdom of God. Secondly, the church has public advocacy, in which it calls on government to execute justice.

These two dimensions, advocacy and witness, should not be confused or conflated. The primary arena of the church’s contribution to a flourishing society will normally be through its witness in its words and deeds. Advocacy can play a critical and decisive role in securing flourishing, as the civil rights movement led by Baptist pastor Martin Luther King Jr. demonstrated, but we must be careful that in our advocacy we do not ask government to do that which is not its responsibility. It is not the role of government to coerce conscience and the church should not ask the government to do this. Advocacy therefore should focus upon justice while witness is the vehicle by which we promote virtue.