Tearfund Australia: From fund to global development partner

Tuesday, 23 May 2023

| Barbara Deutschmann

Why do some movements survive and thrive while others dwindle away? This question prompted this reflection about Tearfund Australia and its journey over 50 years. The story of Tearfund is a story about me and about people like me. The question of why an organisation like Tearfund Australia should continue to thrive since its inception is largely a question of why people like me continue to support it. I have seen the organisation from many different perspectives; firstly as a supported partner when Tearfund Australia supported a community-health program in India where I lived, then as a staff member, a board member, a financial partner, an advocacy participant and a member. The power behind Tearfund has been its ability to respond to and to nurture a community-based movement of passionate people like myself.

In the early seventies, with South Asia in a world of pain, a movement of Christians began to ask more of their churches. Inspired by the Bible and its persistent imperative of justice, Tearfund Australia began as a fund within the coffers of the Evangelical Alliance. The story of the growth from a ‘fund’ to a mature Christian development partnership agency is a testimony to God’s work in our time.

From the start, Tearfund Australia did more than raise and manage donations. Its focus was to educate Christians about global poverty and injustice, and to equip them to develop a biblically based discipleship response. The word ‘fund’ was dropped from its name to express this mission. Steve Bradbury, National Director of TEAR Australia from 1994 to 2008, brought an articulate passion for justice. Under Steve’s leadership TEAR cultivated a grassroots constituency committed to biblical justice. A pioneering board guided the fledgling organisation into a growing understanding of its role as a credible development agency as well as movement of passionate people. One early board member, Bill Stent, spent a sabbatical putting organisational systems in place. Links with AusAID (the former Federal government overseas aid arm) and the growing community of like organisations united through a peak body (now the Australian Council for International Development, known as ACFID) brought training and expertise. Funds, staff, volunteers and resources all grew rapidly through the 1990s and early 2000s. It was not all easy. Steve tells of a time when, with donations levelling and multiple projects needing funds, the staff and board committed to a private 48-hour fast. Within a month, donations had increased and opportunities to speak had multiplied.

I cannot tell the story of Tearfund without mentioning the Really Useful Gift Catalogue. The concept emerged in 1994 from the Bradbury family’s concern to challenge the way Christians celebrated Christmas. The catalogue of ‘gifts’, which became donations to partner projects, educated people about global poverty and discouraged consumerism. It was a wildly successful idea. It raised funds quickly, introduced many people to Tearfund, and brought churches along a journey toward better engagement with global justice issues. It also created a huge headache. For many years income grew rapidly, and then plateaued as other organisations created their own catalogues. The anticipated decline in income risked leaving projects unsupported. The need to focus on raising funds was an organisational shift that challenged many supporters who felt the educational focus would be lost. Finding the balance between the prophetic work of challenging the Christian community about global poverty and maintaining financial resources continues to exercise the Tearfund board, supporters and staff.

Tearfund developed some distinctives within the aid sector. Under Program Director Peter Fitzgerald, Tearfund’s relationships with international partner organisations were shaped by mutual respect. This came from the recognition that the real knowledge about the causes and solutions to poverty lay not in the organisation in Australia but with the partner agencies overseas. It was inappropriate to remotely manage project partners when those partners best knew what needed to be done in their communities. Building dignified two-way relationships with project partners demanded a great deal of travel yet helped the organisation to learn and grow. Project partners were regularly brought to Australia to speak at supporter events.

Tearfund developed another distinctive: it situated project-funding decisions not with its staff but in its supporter community. Project decisions continue to be made through local hubs that utilise the development expertise and wisdom of the Australian supporter base. The saying ‘soft hearts and hard heads’ guide these difficult funding decisions. Strong partnerships have been built through this virtuous circle of mutual learning and appreciation.

The environment in which TEAR was working was changing. At the same time as its work was expanding, many churches and parachurch organisations were shrinking. Christian organisations were facing growing compliance demands but a contracting pool of resources. Some Australian churches chose to engage directly with communities in the global south, ignoring the expertise of agencies like TEAR. Matthew Maury, CEO from 2008 up to the present, steered the movement through this complex environment and brought a strong professionalism to its work. The organisation’s profile in the sector grew as staff were encouraged to work across wider platforms and contribute to the peak body, ACFID. Staff are involved in wider projects that bring no immediate gain to the organisation but help the sector. TEAR was catalytic in establishing advocacy groups like Micah Australia and Micah Global. Matthew Maury has taken the lead in the Emergency Action Alliance which aggregates donations in humanitarian crises and distributes them between agencies in fair ways. The name was changed back from TEAR to Tearfund Australia to activate its links with the international network of ‘Tearfunds’. Meanwhile the spiritual focus continues. Materials to prompt prayer and biblical reflection feed the supporter communities and anchor Tearfund’s work in the Christian gospel.

How do we appraise the reasons for an organisation’s continued existence? Tearfund has survived and thrived under strong leadership and wise governance undergirded by prayer. It has been blessed with committed Christian leaders, staff, members and boards. Both Steve Bradbury and Matthew Maury pay tribute to the ‘exceptional’ boards under which they have worked. These boards aggregated expertise in financial governance, development practice, gender equity, theological reflection and organisational governance. Over the decades they have not been afraid to make brave decisions, such as to work in ‘hard places’, to allow staff to travel to such places, to take prophetic stances to shake people from complacent lifestyles, to adopt campaigns that risk losing supporters, to accept but limit government aid funding, to begin (and end) a fieldworker program and to begin a First Peoples’ program. boards and leadership have shown nimble approaches to a changing environment.

Not all change has been welcome. Some supporters long for a leaner, smaller, organisation better connected to grass-roots membership. Others see the positives in growth and change. Like many others, I can speak personally of its impact on me. Tearfund has brought integrity to my faith. I returned from service in India despairing at how our unequal world could ever be bridged. The Tearfund movement has provided me with opportunities to exercise the Spirit-prompted urges to connect and share. Many of us have felt over the years that, if Tearfund did not exist, we would have had to invent it. Behind that sentiment lies the deeper story of inexorable processes of the Kingdom of God working behind the scenes to probe our consciences and prompt our response.

For many of us, Tearfund’s existence was entirely a work of God. Once alert to the imperatives of Jesus and his Kingdom justice, we needed pathways to put that into practice. It gave ways to respond that stretched our discipleship in interesting directions. Tearfund provided Bible studies, a community of fellow travellers and a way of contributing funds and ideas to grassroots projects in the world’s poorest places. It bridged the distance between Australian town and African village, between Melbourne family and Asian community, and even between Aussie kid and slum child. The Kids4Kids program involved children in immersive opportunities to imagine their lives in another place. Exposure programs took groups of people into the worlds of partners in the global south. Many people testify to the impact of these visits on their lives. The ongoing challenge for Tearfund is to maintain these difficult and expensive initiatives when resources are tight.

Tearfund has helped me exercise my imagination to envisage a better world. In 1997, a global campaign began with the aim to cancel the debt of the world’s poorest countries by the year 2000. Its title adopted the biblical concept of generational release: Jubilee 2000. Tearfund was involved from the start, mobilising its strong supporter base to sign the massive petition that finally led to the cancellation of over $100 billion of debt. The Micah Challenge to halve global poverty by 2015 drew on the prophet Micah’s words to ‘do justice, love mercy and walk humbly with the Lord’. Renew Our World was a campaign for sustainable and equitable economies. These are just some of the campaigns whose names and ethos stretched our imaginations to visualise a world where poverty was eradicated and everyone was equally valued.

Tearfund Australia’s success testifies to the impact of a civil society movement in tackling global problems. The links forged between a supportive Christian community in Australia and frontline agencies in the global south have built a Christian witness of which the Australian church can be proud.

Barbara Deutschmann is a post-doctoral research associate with the University of Divinity working in the area of gender in the Old Testament. She shares life with partner, Peter, three adult children and a clutch of grandchildren.

Photo credits

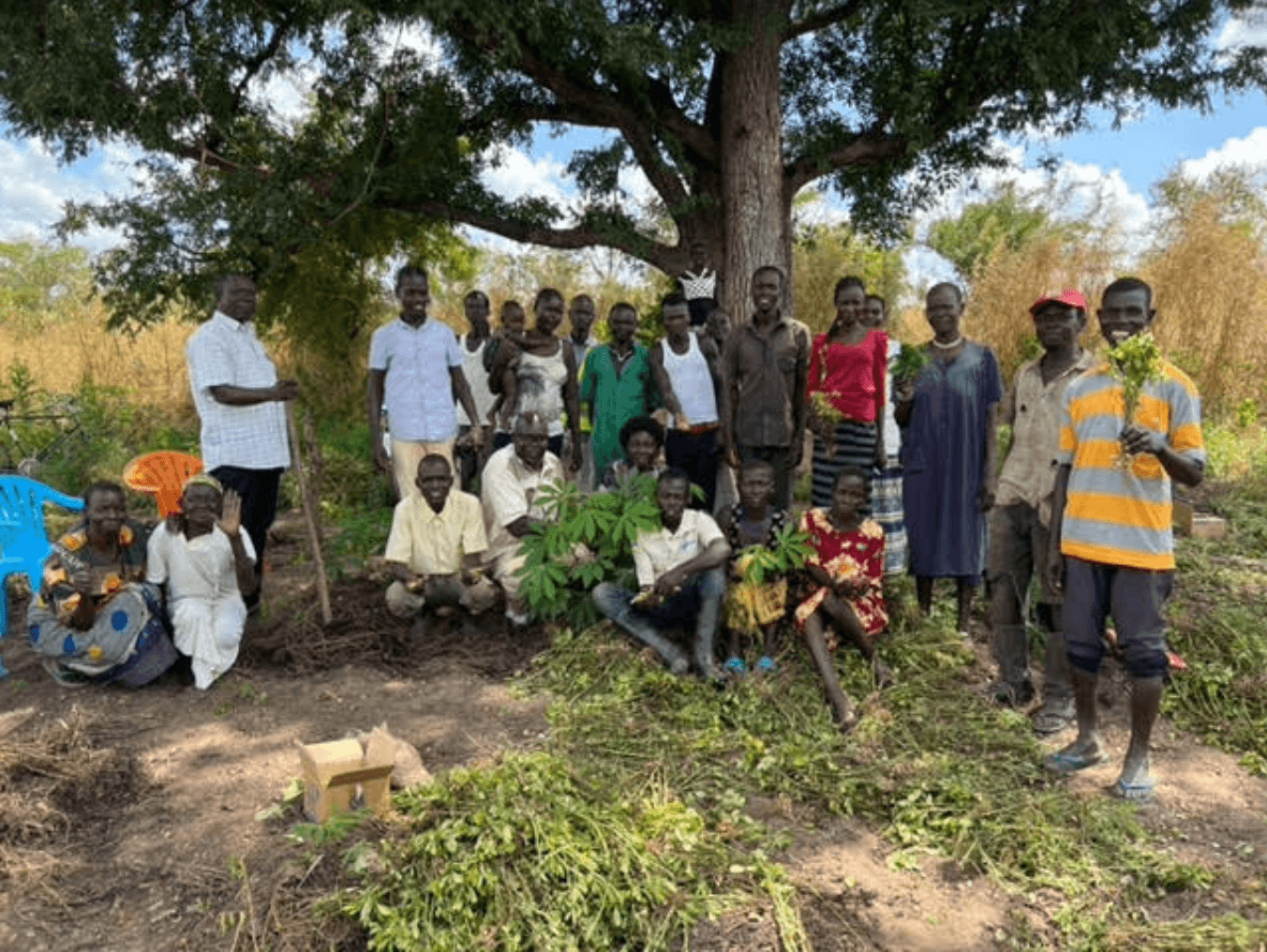

Farmer Group (South Sudan): In the midst of significant challenges such as hunger and insecurity, Tearfund’s partner Sudan Evangelical Mission is supporting Farmer Groups like this with skills, knowledge and opportunities to build resilience. Photograph: Marshall Currie.

Micah Summit: In November 2022, a group of young leaders were supported by Tearfund Australia as delegates to the Pacific Australian Emerging Leaders Summit, a joint initiative of Micah Australia and the Pacific Council of Churches. Photograph: Tearfund Australia.

This article first appeared in the May edition of Equip magazine. To receive your copy of this issue, which includes the stories of innovative Christian Movements from the 1960s to 2000s, subscribe here. We apologise to TEAR and author Barbara Deutschmann that the two pictures included with this article and the correct byline were missed in the Equip version.