Book review: Singing the Psalms with my Son: Praying and Parenting for a Healed Planet

Friday, 8 December 2023

| Claire Harvey

Singing the Psalms with my Son: Praying and Parenting for a Healed Planet

By T. Wilson Dickinson

(Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2023)

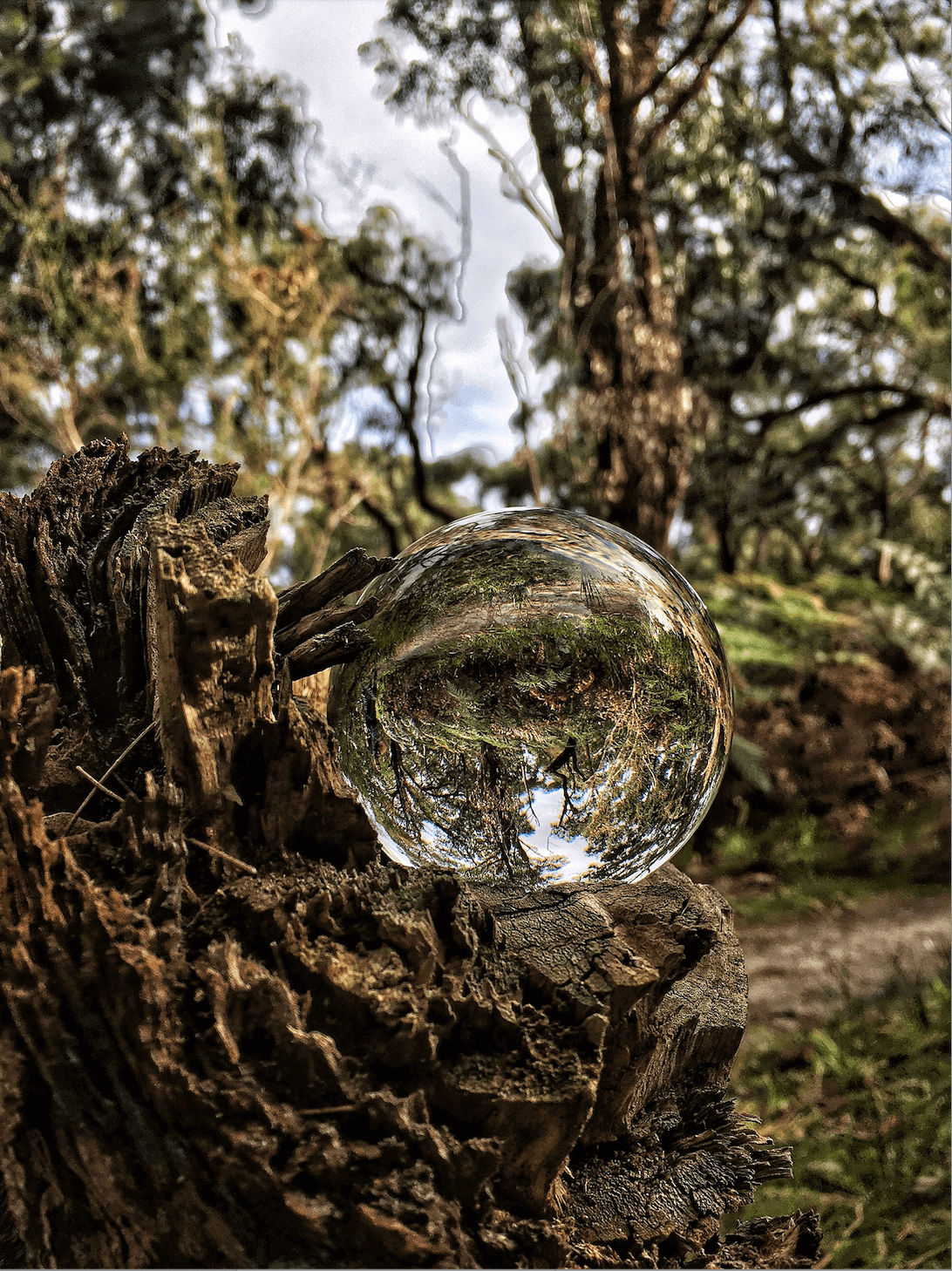

Having read and appreciated Dickinson’s 2019 publication The Green Good News: Christ's Path to Sustainable and Joyful Life, I was looking forward to receiving a review copy of his latest book, Singing the Psalms with My Son, despite not being particularly grabbed by the title. As much as I do have a son of my own, and I certainly appreciate the breadth and richness of the Psalms, I couldn’t help but feel that this book might have a strong ‘father-son’ flavour to it, as depicted by the cover image. It turns out that this book very much features a growing father-son bond, yet there’s something disarming and inclusive about the raw honesty and emotional vulnerability expressed by Dickinson. He demonstrates great skill in holding in tension the huge challenges facing humanity along with the daily pressures felt by many households, expressing a rare combination of intellectual honesty, personal courage and deep pastoral sensitivity.

T. Wilson Dickinson is a theologian, pastor and organiser based at Lexington Theological Seminary. He is also a husband, a father and an uncle. As much as Dickinson’s professional qualifications attest to his capacity to speak to theological matters with wisdom and expertise, what I found most refreshing and compelling about this book was the skilful way in which he interweaves scriptural insights with stories from the very grounded context of his multigenerational experience of home, including the joys and demands of life with a young child. There is nothing remotely abstracted about this short but rich text: its 93 pages echo so much that will be familiar to so many parents, including ant-watching and blanket-forts and simple-joys-amidst-sleep-deprivation. This one paragraph typifies Dickinson’s brutally honest style:

The emerging realities of climate change are terrifying. When I look upon the future with my son in my mind I am simply overwhelmed. I find myself stuttering and stammering. In such matters I am unschooled and unprepared. On the contrary, the training I have received often leads me to avoid the reality of such problems as I busy myself serving the structures that are causing the ecological crisis in the first place. (p. xiv)

Chapter One: ‘Finding Alternative Energy’ names a crucial paradox of contemporary parenting, which is that a parent’s love for their child can be simultaneously overwhelming AND motivating in terms of our response to the various ecological catastrophes unfolding in our time. Psalm 23 provides imagery of simplicity and joy, and offers the assurance of nourishment and rest. ‘Just and joyful’ emerges as a key phrase, along with a central theme of shared life, in community:

‘We need communities that help us begin to incarnate the changes we want to see and that will cultivate long-term capacity to push for systemic change. Therefore, we need to look for practices and processes that enable us to live together in ways that are just and joyful. Transformed, beautiful, resilient, and just shared lives and communities, then, are both the means and ends of addressing climate change’ (p.3).

Chapter Two: ‘Wondering in Creation’ draws us to the art of paying closer attention to that which is right in front of us, which Dickinson refers to as an ‘orientation of childish wonder’ (p.11). As much as this can be a source of boredom or impatience for some parents, the invitation is to develop our curiosity and hopefulness. Psalm 100 exhorts us also to see, and to hear, and to sing with gladness. Readers are reminded that ‘joy is not the same as happiness’, and that ‘Our joyful noises come not just from positive feelings but also from the practices of faith, hope and love in the race of fear, regret and loss’ (p.15).

Chapter Three: ‘Giving Voice to Muted Suffering’ takes a deep dive into what Dickinson refers to as the ‘waking nightmare’ that was the 2016 presidential elections (p.16). I couldn’t help but note some similarities to our recent referendum on the Indigenous Voice to Parliament. Dickinson doesn’t hold back in expressing the full range of his emotional response, including the following confession: ‘The macabre and devastating thought entered my mind that perhaps we had made a mistake by bringing a child into this world. … looking at his future, thinking about the violent, cruel, and fearful world that he would face was too much’ (p.17). Psalm 13 presents an example of taking our pain, confusion, bewilderment and impatience, and directing it to God. Dickinson suggests that prayers of lament enable us to break through our apathy, forming a sense of protest against the status quo (p.20) and helping us to forge a new and more hopeful path.

In Chapter Four: ‘Cultivating Peace and Power in the Everyday’, Dickinson recalls the early days of parenthood, where ‘cries for care’ present almost constant interruptions to normal routines. He speaks of the intimacy of providing sustenance for a vulnerable baby, referring to these precious times in his life as ‘orienting moments of a new order of life, moments where our interdependence was incarnated and trust was being built’ (p.24). Counter to the dominant narratives of our market economy, which are centred around productivity, Dickinson suggests that learning to attend to such cries may sensitise us and ‘build up our capacity to hear and respond to the cries of the earth and her peoples’ (p.24). He provides Psalm 131 as an example of turning away from grandeur and power to instead find ‘rest and peace in the practices of care’ (p.29), which are constructive and generative acts.

Chapter Five: ‘Showing Right from Wrong’ calls out the ongoing tendency to blame environmental destruction on individual actions (or lack of action), rather than on ‘unjust structures that necessitate exploitation and extraction’ (p.33). Dickinson points to the powerful stories that shape us, with prevailing social expectations reinforcing the false narrative that our homes ought to shine as domains of security and success. In stark contrast, Psalm 15 presents us with the wicked (who are rich, cruel and clever) and the just (who are honest, peaceful and generous): ‘The backdrop of a beautiful and just creation animated by a loving Creator transforms the wealthy from being winners, into wicked exploiters who have made a mess of things’ (p.35). This is a one of a number of places where Dickinson begins to unpack the stories we’re told about success and what it actually looks like to live a good life.

In Chapter Six: ‘Flipping the Script on Success and Happiness’, Dickinson digs deeper into this idea of the scripts that are written for us by others. These subtle, and occasionally not so subtle, expectations are referred to as ‘monstrous little voices that whisper in our ears’ (p.42), and here readers are introduced to a new refrain: that of success and supremacy. Dickinson suggests that it is often children who can help us to see more clearly, as ‘they are still learning these scripts and have not fully accepted or memorized them’ (p.43). Psalm 37 counsels us not to fret, or burn with jealous anger, or be provoked to imitation, for the abundance of the wicked is fleeting, and there are consequences to violating God’s moral order. Dickinson boldly suggests that ‘the psalmist does not simply charge us with resistance, but also with re-existence’ (p.47).

I confess to quietly weeping my way through much of Chapter Seven: Crying Tears of Guilt and Hope. Dickinson introduces the idea of climate disavowal, which he defines as ‘a process whereby we stuff down the scope and real sources of climate change’ (p.51). He suggests we need prayers that are more honest, despite this process of facing-up-to-things being confronting, terrifying and painful. He draws on the brutal desperation of Psalm 130, where the poet cries out from the depths from what feels like incredibly shaky ground. Yet penance, compunction, confession and repentance can help lead us to repair, healing and transformation: Dickinson reminds the wounded and the weary that ‘a reorientation to the goodness of God as the true source of our sustenance and joy can sustain us’ (p.57).

Chapter Eight: ‘Celebrating Holidays’ is particularly pertinent in its honest exploration of our celebratory habits and an acknowledgment that they have, on the whole, become powerful symbols of our rampant consumerism (and the extraction, exploitation, degradation and destruction that are now necessarily built into global supply chains that serve ever-increasing appetites on a finite planet). Dickinson is again brutal and piercing in his insightful honesty: ‘For professional-class parents, staging the perfect childhood is often a way to deal with deep anxieties about the future’ (p.67). In contrast, our attention is drawn to Psalm 96 which invites us into a procession where the goal is ‘offering up and giving over’, including singing and sacrifice. ‘Such a picture, however, begs the question: what do you give to the deity who has everything? Perhaps the best thing we could give to the Creator would be to care for her creation’ (p.68).

Chapter Nine: ‘Playing and Working for a Different World’ draws readers into the magical world of blanket forts, highlighting the importance of lightness and play where degrees of silliness are completely acceptable. ‘In the space of play the pressures of productivity and efficiency are at least partially lifted. In this lighter space there is a greater sense of collective participation, whimsical engagement, and the centering of delight and beauty’ (p.73). In allowing ourselves to get lost in our imaginations and to see new possibilities emerge: new possibilities are what echo through Psalm 104, which depicts a world that overflows with God’s wisdom and creative power. Other creatures are a part of this world, and the reality is that we are tasked with sharing this earth in humble, grateful interdependence.

The final chapter, ‘Sowing the Seeds of Change in Social Spaces’, provides readers with insight into the particular shape of Dickinson’s household, and their brave collective journey toward living out their values in more faithful and faith-filled ways. Dickinson’s experience invites us to truly believe that ‘Living in and being shaped by this common life cultivates a sense of trust that we can find sustenance and security not just in exchanging our labor for a wage, but also in simplifying and sharing’ (p.84). The powerful imagery of Psalm 133 calls us to unity and to living with a sense of having been ‘anointed for a purpose the wider world’ (p.87). Very aware of the challenges that come with intertwining our lives with other broken, messy, people, Dickinson communicates a stubborn hopefulness that sharing common life, collaborating for the common good, trusting love, making peace, cultivating joy and attending to our fellow creatures are all central to our hope for the future.

Very helpfully, Dickinson’s latest book concludes with two appendices. The first offers instructions on how one might read the psalms more prayerfully, encouraging reading in community as the best approach, including the ancient practice of the lectio divina as a way to read more ‘prayerfully, playfully, and patiently’ (p. 106). Appendix 2 offers spiritual exercises for both personal and communal engagement with the text. These are incredibly helpful resources for groups that might look to utilise this text as part of their regular bible study or home group gatherings.

As someone who has walked a long and often-fraught journey of learning to care more for God’s creation, including a range of challenges that seem to be magnified when seen through a parenting lens, I thoroughly appreciated the raw honesty contained in these pages. I was particularly surprised by Dickinson’s willingness to engage in profound and unashamed emotional honesty about his own responses to the wonderful mess that is our world and to the precious little human that has been entrusted into his care. With levels of eco-anxiety continuing to climb, as extreme weather events keep making headlines around the globe and as world leaders argue about what approaches are likely to be effective, feasible and fair, this really is a crucial text for our unique times.

T. Wilson Dickinson makes a compelling case, by way of a journey through a selection of Psalms and seen through the lens of his own kin-dom, that simple-yet-generous shared life is a supremely loving, wise and faithful response to our unfolding ecological crisis. It may, in fact, be the only way forward for us as God’s creatures. This book moves well beyond the ‘why’ and ‘what’ of climate action, presenting touching and transformative glimpses of shared responses that cut right to the heart of our increasingly complex ecological and economic mess, highlighting the spiritual and relational resources that might just save us from ourselves.

Claire Harvey serves on the Boards of Ethos and CoPower, is a councillor at Frankston City Council and the Chair of the South East Councils Climate Change Alliance (SECCCA). Claire carries ongoing concern about the prospects of future generations as a consequence of our changing climate: her son, Micah, will be 88 at the turn of the century! She has a M. Div. from the Bible College of Victoria (now the Melbourne School of Theology. Claire’s latest venture, ECHO Coaching, seeks to create sacred space for honest conversations around work, life, purpose, spirituality and ecological care.

Image credit: Jasmine Coates.