Why would you give a convict a gun? A reflection on reading Truth-Telling by Henry Reynolds

Thursday, 22 June 2023

| Sue Edmondson

When we drive from Canberra to Mallacoota we pass a sign pointing to Mt Cooper about 15 minutes out of Nimmitabel, now a town with a service station. Mt Cooper was a station that was part of the huge grant of land to the Campbell family, of Campbell's Wharf in Sydney and of Duntroon, to compensate them for the loss of cargo when one or two of their ships loaded with wool and other items were commandeered to sail quickly to London, or anywhere I suppose, to bring food back to the starving early colony. It is ironic, if not so tragic, to consider that the land's First Peoples got by quite well without such supplies.

My convict ancestor, Donald Rankin, was once an overseer at Mt Cooper and is buried there, the first convict burial on the Monaro. I remind myself of the gift to our family of our survival in Australia and am thankful. There is a sign to the property Glencoe a little further on, named after the place from which they came, and we cross a Native Dog Creek, along which Donald's own property, Native Dog Flat, was located. It was when my own father, Donald Rankin (one of generations of Donald Rankins), died that I gained some sense of belonging, survival and continuity, the ongoing hand of God on our lives from the presence of that earlier Donald to the absence of the one I knew.

Like Henry Reynolds, I studied history after high school, but in order to teach at the junior secondary level. We arrived back for our second year to discover that both primary and secondary teachers-to-be were to study the same Australian Studies course, and it was a remarkably innovative course for the time and the institution. Donald Horne's The Lucky Country was one of the key texts, and the purpose of teaching the routes of the explorers – bread and butter primary school curriculum stuff – was questioned. Aboriginal Australians were completely absent from the course, however, as they were from the curriculum in general, except where they met up with explorers, and if explorers dropped off the curriculum, then the First Peoples in the country dropped off also.

The 1965 Freedom Bus Ride, led by Charles Perkins and filmed by James Spigelman in 8mm, took place the year before and had been reported on daily on black and white TV. Yet not even the stirrers in the group queried the absence of Aboriginal history. The speakers at assemblies in 1966 included Manning Clark but no leaders of the campaign for the 1967 Referendum.

There was one curious aberration, however. One Saturday morning we put on our duffle coats and missed breakfast to visit a kitchen midden on the banks of a lagoon on a local property in the Riverina in the thick of a morning fog. It was magic. The lecturer, who was active in local history, was the first person in my life to give any credence to the idea that Aboriginal people had lived in NSW. But then he also taught pre-history and archaeological methods, so there was no sense that we were dealing with anything other than the time before time, which meant it had no relevance to the present.

I began teaching in 1967, completely oblivious to the Referendum (we were too young to vote), and we could not afford newspapers or radios. But by then I had become aware of the government settlements on the edge of towns as I had joined an ecumenical work camp to build a house in Moree in the holidays. The social studies course placed Aboriginals in the neolithic age and the textbook had paragraphs on 'smooth the dying pillow' and 'assimilation', but it was a presence that signified absence.

How this 'great Australian silence' came about is one of the subjects Henry Reynolds addresses in Truth-Telling: History, Sovereignty and the Uluru Statement (Sydney: Newsouth, 2021, p. 162), but he is unable to entirely account for it. The emotionally charged public discussion of the murder of Aboriginals in the 19th century, the rightness and wrongness or ‘necessity’ of it, had disappeared, and historians had agreed that 'a veil should be drawn over the past'. It most successfully was for the first 60 years after Federation.

My grandfather delighted in his first car when he retired and went on frequent trips through the Monaro to visit relatives and once-familiar places, calling in on us on the way. 'When you want to know where you come from’, he said, ‘it is the Monaro’. By then I knew we had to have come from somewhere else first (my mother's parents were English migrants), so I asked him. He gave no answer. Since then, our family historian has assembled documents that fill many gaps. Australia's convict records have been listed on UNESCO's International Memory of the World Register. Births, deaths, marriages and census records can be produced from the 19th century. In contrast, Aboriginal deaths by the hands of white settlers in the 18th and 19th centuries were not counted by the state which had assumed sovereignty, let alone recorded by name, date or place. It was unclear whether the rule of law even applied to them.

Dispossession, deaths and separations (and I am using the more polite terms), continuing into the present day, must have a profoundly different effect on the sense of self and family than I have experienced. My relatives, however poor or prosperous, were able to look after each other and had legal rights and agency; societal changes tended to favour our survival. Even transportation worked for us. This was not so for First Nations peoples, and I have needed them to tell me this.

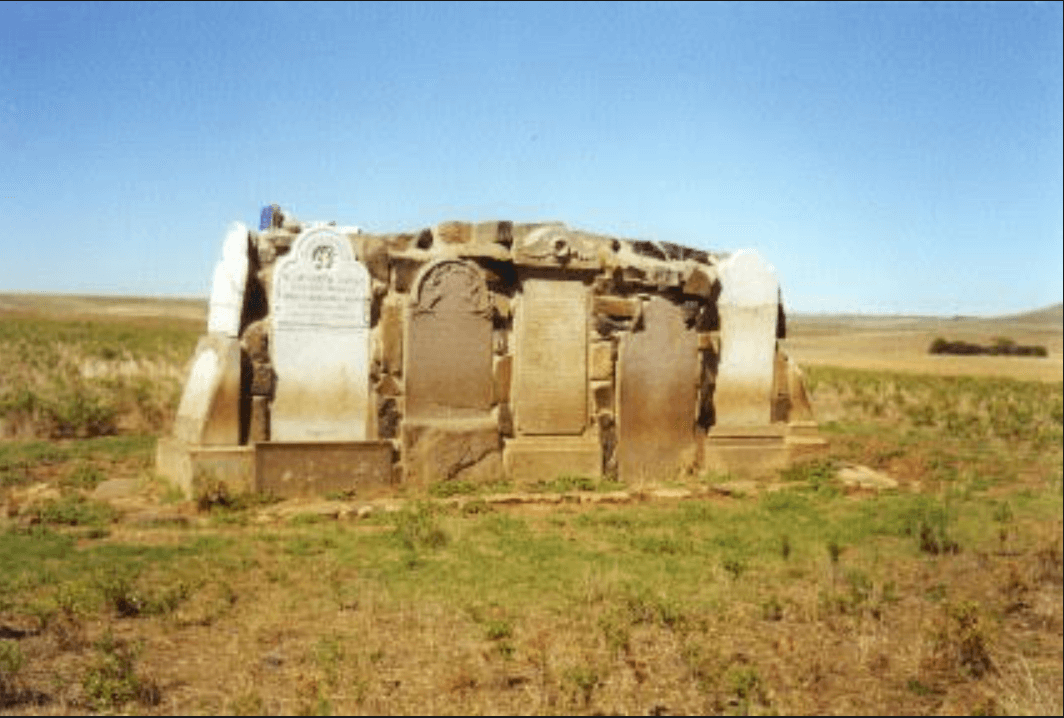

The marked graves of my relatives that dot the Monaro are witness to lives past, lived on and buried in stolen land; nobody bought it or received it via an agreement or a treaty. Reynolds outlines why the lack of an agreement or treaty was unusual and what it might have meant - perhaps land for a convict settlement, and not the grand colonial project, for one thing. What actually were Phillip's orders? War memorials are ubiquitous on the Monaro along with annual remembrance ceremonies, but nowhere is there a visible memorial to the original owners who died.

I have been moved by the acknowledgement of country as it has developed through various phrasings and emphases appropriate to contexts, and by different speakers. The phrase 'for which sovereignty has never been ceded' was confronting when I first heard it and still is. Reynolds examines this question in detail from a western perspective. Was it acceptable for a European, or any, power to claim sovereignty over anyone, or to assert a right to live somewhere that was not legally theirs? On a number of levels, Reynolds disabuses me of any fantasy that claiming Australia, or the east coast, for another power, or gradually occupying it by force, was legal or acceptable for the times – the accepted narrative of my childhood. Governor Phillip and his successors were confronted with questions that bureaucrats 'at home' were unable to address ethically, consistently or in a timely manner. Governors were conflicted. Settlement of Australia was built on a number of unworkable principles and depended on being undertaken by force. It was not 'a uniquely peaceful history', as our newly published college text by Russell Ward in 1966 asserted (p. 166).

Donald Rankin was granted his ticket of leave after bringing in two escaped convicts at the point of a gun. Was he a snitch or had they had enough? By then applications had been made for his wife and grown children to migrate, perhaps even before Robert Campbell, who was a member of the first NSW Legislative Council, began advocating publicly for a ‘better’ class of settler to be encouraged, to develop the land further. It would be much easier for such settlers to establish themselves with freedom to move and a certain dignity. To this day I am amazed that they all came, spouses and children. Was it desperation, a stubborn commitment to the family or the promise of owning their own land?

I had puzzled as to why Donald had a gun. To shoot rabbits? Not sheep, as he was guarding them. To shoot an animal to eat? Or to bring back convicts? There is no doubt after reading Truth-Telling that it was at the very least for protection, and at the realistic worst for shooting Aboriginal people who stood in the way of advancing settlement – no questions asked.

I do no justice to the depth of Henry Reynold's sustained and ground-breaking research and the lucidity with which he presents it in plain sight. I had no idea how ignorant I was, and how undeniable is the evidence of the frontier resistance and the ongoing unlawful killings. I can only thank him for having the curiosity and the will to pursue this study, and the friendships with Aboriginals, Torres Strait Islanders and others in the deep north who have contributed to this task. Reynolds has carried the burden of being regarded as a ratbag, and far worse, in the pursuit of truth. This book is one place to start the truth-telling hoped for in the Uluru Statement from the Heart. That description of sovereignty as 'a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land … and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples', offered in the Uluru Statement from the Heart and confirmed by the High Court, gives the impetus for this book.

I look forward to engaging with This Whispering in our Hearts Revisited (Newsouth, 2018), to meet others who have questioned the status quo and have grappled with conscience and action – as we now have to do if we are to pursue the path set out in the Statement from the Heart, which we are most graciously invited to do.

Sue Edmondson lives in Canberra on Ngunnawal and Ngambri country, where she and her husband Ray are engaged in advocacy for the national memory institutions, especially the National Film and Sound Archive. Sue is almost a foundation member of Zadok, having been given a subscription to publications for a donation of five dollars in 1977. It has been a gift that keeps on giving as she has been a subscriber and supporter ever since. She worked as a volunteer in Zadok’s Canberra office and has been a member of the board.

Image credits

Headstone wall at the Mt Cooper cemetery near Ando, NSW.

Empty cemetery marked by the lone tree with the headstone wall on the right.

First published at http://monaropioneers.com/Cemeteries/MountCooper/MountCooper.htm. Used with permission.