Why I’m happy when house prices fall

Wednesday, 24 April 2019

| Jon Eastgate

I have spent most of the past 30 years working in one way or another to improve housing options for low-income Australians, including those who are homeless or at risk of homelessness, so I follow what’s happening in housing fairly closely.

If you rely on the Australian media and our political leaders for an understanding of housing issues, you are likely to be confused. In the lead-up to the last election, we were flooded with concern about house prices being too high, squeezing out first home buyers. Now house prices are falling, and we are swamped with worried faces and scare campaigns.

Meanwhile, every now and then, seemingly unconnected to all this housing market angst, we see stories from time to time about people sleeping on the street, and worthy charities bringing them hot soup and warm coats.

As Christians, how are we to make sense of this, and how should we respond?

Setting our Compass

Housing policy is complex, and often the interests of different players in this field are in tension. Substantial amounts of money are tied up in housing and it has made some people very wealthy. It is a cornerstone of our financial system. Yet it is also a way of simply providing safe, secure homes for ordinary people, rich and poor.

In setting my compass on this issue, I find it helpful to remind myself of whom I should be most concerned about. As a follower of Jesus, I think of Paul’s words in Philippians 2:

In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus:

Who, being in very nature God,

did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage;

rather, he made himself nothing

by taking the very nature of a servant,

being made in human likeness.

This is not just a fascinating piece of theology. Jesus and the apostles (like the prophets before them) make it very clear that living as followers of this Christ entails ‘making ourselves nothing’, giving a special place to those who are poor and humble. Some words from James provide a good example of this teaching, although if space permitted I could cite plenty of other examples.

Suppose a man comes into your meeting wearing a gold ring and fine clothes, and a poor man in filthy old clothes also comes in. If you show special attention to the man wearing fine clothes and say, ‘Here’s a good seat for you,’ but say to the poor man, ‘You stand there’ or ‘Sit on the floor by my feet,’ have you not discriminated among yourselves and become judges with evil thoughts? Listen, my dear brothers and sisters: Has not God chosen those who are poor in the eyes of the world to be rich in faith and to inherit the kingdom he promised those who love him? But you have dishonoured the poor. Is it not the rich who are exploiting you? Are they not the ones who are dragging you into court? Are they not the ones who are blaspheming the noble name of him to whom you belong? (James 2:2-7)

It is clear to me that when we assess any policy area, including housing, we should look at how it impacts on the poorest and most vulnerable people in our community, and not be too concerned about preserving the wealth of the wealthy.

Feast for the rich, crumbs for the poor

The current frowns about falling house prices, especially in Sydney and Melbourne, need to be seen in the context that prices are historically high. In the late 1980s the average purchase price of a house in Australia was less than three times the average annual household income. In the years since, this ratio has climbed to over 5 times household income, far higher in some places. Not surprisingly, home ownership rates have gradually fallen over this time from over 70% of households in the 1980s to just over 60% in the 2016 census. This means more people rely on the rental market than in the past, and they rely on it for longer. Rents have not increased as fast as prices, but they have also increased faster than incomes.

Source: https://www.rba.gov.au/chart-pack/household-sector.html

As a consequence, more people struggle to afford housing. Over a million low income households (those with the lowest 40% of incomes) pay more than 30% of their income for their housing, including nearly 400,000 households with a mortgage and over half a million private renters. This is particularly tough on renters. At least if you are paying off a mortgage you are deferring gratification and you have the security of a permanent home after a few years of struggle. If you are renting you get no asset for your toil and can find yourself asked to leave at short notice. Many people can’t even find somewhere to rent - over 100,000 Australians were counted as homeless on Census night in 2016, with many more at imminent risk of homelessness. It will come as no surprise that certain groups of people are more vulnerable in this situation – single women (with or without children), Aboriginal people, people with disabilities or chronic illness, refugees. Our housing system reflects and exacerbates our social inequalities.

Housing policy is complex, but I’m going to oversimplify it here. We have achieved this result because it is what our governments’ housing policies are designed to do.

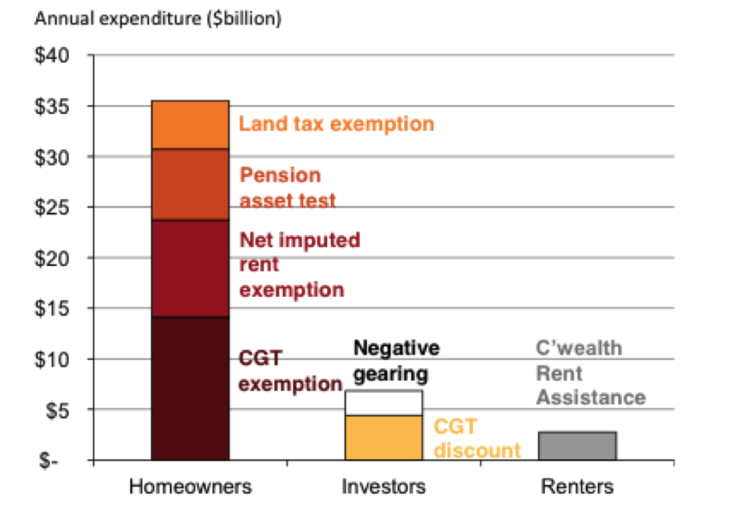

Of course governments don’t articulate it that way and it may not be entirely intentional. Nonetheless, if you follow the money this is where it leads. In rough terms, Australian governments spend about $45-50b per year on subsidising housing either through direct payments or through special tax treatment, mostly the latter. Over $35b of this goes to owner-occupiers in the form of exemption of the home from capital gains tax, land tax, the pension assets test and not taxing the ‘imputed rent’ – that is, the value the owner gets from living rent-free in their own home. These subsidies are not means tested, and increase with value of your home, as well as benefitting outright owners more than those with mortgages. The richer you are, and the swankier your home, the more you get.

The second largest set of subsidies (worth around $7b) goes to rental investors, who are able to offset their losses against other income in order to reduce their tax (negative gearing) and then, when they sell the property, pay capital gains tax at half their top income tax rate. This arrangement creates an incentive to use rental housing as a speculative investment (wearing losses now in the hope of future gains) rather than as a long-term secure income stream. It also limits rental investment to individuals, since institutions such as super funds don’t get the same tax breaks. Hence the market is inherently unstable, with investors needing freedom to sell at the right time, so it can’t provide any genuine security for its tenants.

All of this subsidy for wealthier people tends to draw investment into housing, especially when interest rates are low and finance is easy to get, driving inflation in prices and rents.

Meanwhile, subsidies for the poorest people are comparatively niggardly. The Commonwealth spends around $3-4b per year on rent assistance to those on pensions and benefits, and around $1b a year subsidising social housing with this figure matched by the State and Territory governments.

Neither of these subsidies comes close to meeting the need. Rent assistance has not increased as fast as rents so it has become less adequate over time – about 40% of those who receive it still pay over 30% of their income in rent. The level of Commonwealth and State funding for social housing is barely enough to keep the system ticking over. There has been little growth in the amount of social housing since the 1980s, and what exists is getting older and more run-down. As a result, housing departments have to ration the housing so strictly that only the most highly disadvantaged get access. This leaves many people with no option but to resort to an overstretched homelessness service system that can often only patch up their immediate crisis, not solve their basic housing problem.

Source: ‘Renovating Housing Policy’, Grattan Institute, October 2013, 22, https://grattan.edu.au/report/renovating-housing-policy/. While the numbers are likely to be a bit higher now, the overall picture is unlikely to be any different as there has been no significant policy change.

So, we have a set of policies around housing that increase housing values, then give people on the lowest incomes a few crumbs to partly mitigate the damage. Surely we can do better!

What Needs to Change?

The inequity in our housing system is long-term and entrenched, and solving it will take a long-term vision. A brief correction in housing prices before they resume their upward climb will not cut it. Of course as I say housing policy is complicated, but here are four things I think we need to work towards.

- We need a sustained slow fall in house prices. We don’t want them to fall precipitously as this would trigger a banking crisis from which no-one would benefit. Rather, just as they have risen steadily in relation to incomes for over two decades, we need them to fall steadily over the same period, or at least to stay the same as incomes rise. One way of helping to do this would be to take some of the subsidies out of the system – for instance, by applying land tax to owner-occupied housing, and charging capital gains tax on high-end housing. It would also help to reform the tax treatment of rental investment as discussed below.

- We need to rebuild the private rental market as a long-term, secure housing option. Partly this would be helped by stronger tenancy laws, but more fundamentally it needs a shift in investment from speculation on capital gains to generating a steady rental income. This would be easier if house prices didn’t rise, and it will also be helped by the type of policy advocated by housing organisations for decades and now taken up by the Labor Party – limiting negative gearing, increasing Capital Gains Tax.

- We need to revitalise social housing. We need to put serious extra money into building more of it over an extended period. We need twice or three times as much new money in the sector than what we have been seeing, and we need it over ten or twenty years. Only a robust social housing system, available to all who can’t afford private housing, can ensure that the most vulnerable people are securely and affordably housed.

- We need to house people who are homeless, not just help them survive homelessness. At the moment a lot of government and private resources go into services that provide meals, laundry facilities, clothes or short-term accommodation while leaving the person’s fundamental lack of home unaddressed. These programs are better than nothing but it is clear that what works best for homeless people is to provide them as quickly as possible with a secure permanent home, along with the support they need to rebuild their lives.

Conclusion

Jesus directs our gaze towards the poor and humble. Meanwhile our governments direct housing resources to the wealthy and powerful. The way to change this is not a mystery; housing advocates have been pointing it out for decades. We just need to get on with it.

Jon Eastgate is a partner in 99 Consulting and has worked in and around the not-for-profit housing sector for more than 30 years. He lives in Brisbane and worships at St Andrews Anglican Church, South Brisbane.