The Gulf Between Us and the Poor

Monday, 11 July 2011

| Siu Fung Wu

I don’t want people to become poor, because I have seen enough human misery. I belong to a community where a significant number of people suffer from economic hardships because of their disadvantaged social status. I met a lady recently whose son suffers from mental illness. They live in public housing and life is hard for them. A friend’s mother is currently seriously sick in Burma, and it has cost my friend a fortune just to send her to the hospital. I feel for them because I was once poor – not destitute, but poorer than most people I know in Australia – and I know the helplessness of living in a world where the rich and powerful call the shots.

Two views on one cartoon

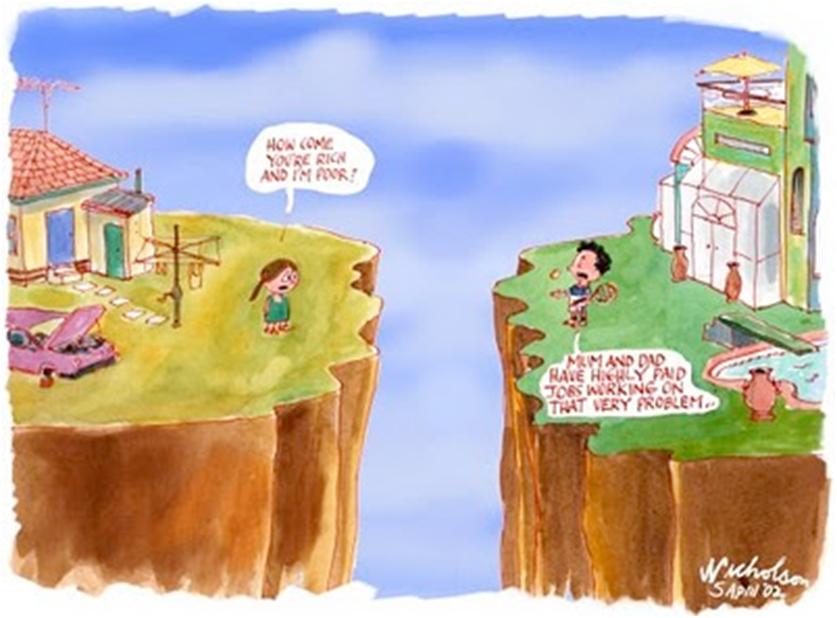

My job takes me to different theological colleges to talk about poverty and injustice in the world. Last year I showed a cartoon to two different groups of students (see below). In the cartoon there are two cliffs facing each other. There is a big gulf between the cliffs. On the left cliff there is a girl living in poverty, with a broken-down car and a rundown house in the background. On the right there is a wealthy boy, whose house is luxurious, with a swimming pool next to it. The girl shouts to the boy, "How come you are rich and I am poor?" The boy answers, "Mum and Dad have highly paid jobs working on that very problem."

The discussions I had with the two groups of theological students were very interesting. I explained to the students that the majority of us in Australia were much wealthier than lots of people in the rest of the world, and I invited comments on the cartoon. In the first group, the students focused primarily on the boy. We spent a lot of time saying that there was nothing wrong to be rich. We reasoned that we needed people with professional skills to deal with the complex issues of global poverty, and they had to be paid accordingly. Much of the discussion was about ensuring that there was nothing wrong to be middle-class Australians.

In contrast, the second group of students focused on the girl on the left. They acknowledged the dilemma we middle-class Christians faced in the West—that we were relatively rich and countless people in the world were poor. But we spent a lot of time talking about the plight of the girl and what we could do to help people like her. We looked at the life of Jesus and sought to learn from him. One lady's comment was profound, "We need to ensure that the voice of the girl can be heard." On reflection, I wonder whether the voice of the girl was heard by the first group of students.

The Scripture and the poor

I am sure that the students in both groups are sincere Christians. And I have no problem for people in the aid and development sector to earn a reasonable income. But over the years I have learned that the gulf between the rich and the poor is not simply an economical one. I do believe that Scriptural truths are universal and the poor do not have moral superiority over the rich, and hence at least in theory our material affluence should not adversely affect our ability to understand the Bible. But I wonder whether our wealth can be a hindrance that stops us from fully understanding the plight of the poor and the Scripture.

The writers of the New Testament had an advantage over us in this regard. In his latest research on first-century Greco-Roman world, Bruce Longenecker estimates that about 65% of Christians in the Pauline house churches lived at or below subsistence level, and 25% at “stable near subsistence level”. Only 10% had moderate surplus.[1] While these are estimates only, they are not inconsistent with the situation of an urban community in the pre-industrialised world. Longenecker goes on to say that the apostle Paul would have had a degree of financial security, but in his ministry he would probably have moved down to a living standard that was at or below subsistence level.[2] This means that Paul’s eagerness to remember the poor in Galatians 2:10 did not stem from an abstract theology, but firsthand experience.

But it is the story in Luke 16:19-31 that is most telling. Just like the cartoon described above, there was a gulf between the rich man and Lazarus. Before they died the gulf was, metaphorically, the gate of the rich man’s house. I grew up in a neighbourhood where the rich lived within walking distance from us. They lived in their comfortable homes and never had to enter our small apartments to see what it was like. They might be very kind-hearted people and would be generous to the poor. But they would not have known what it meant to be poor. Thus it is very likely that the rich man did not know the suffering of Lazarus simply because of the huge social and economic gap between them. Their lives were miles apart, even though they were neighbours.

But it seems that the rich man in Luke 16 has no excuse to be ignorant, for Israel’s Scripture has clear instructions to care for the poor. After death there was a great chasm between him and Lazarus. The former suffered in Hades, while Lazarus enjoyed being in Abraham’s bosom. The rich man asks Abraham to send Lazarus to warn his brothers. But Abraham said to him, “If they did not listen to Moses and the Prophets, they will not be convinced even if someone rises from the dead.”[3]

Blind spots

I don’t think Christians in Australia share the same attitude as that of the rich man, and I think it is unhelpful to criticise the wealthy as if they should be guilty for their material possessions. But perhaps we do share the same blind spots regarding the plight of the poor and the Scripture. For the Scripture says that Jesus sees the giving up of possessions as part and parcel of discipleship (Luke 12:33; 14:33), and that he spends time with the crippled, the blind, the lepers and the widows – the most vulnerable in the ancient world. Indeed Jesus was born in a manger (a feeding trough for animals) and a refugee to Egypt. To follow Jesus means to follow his way of life, and material possessions should not get in the way.

So, what does it mean to us today in light of global poverty, where 24,000 children die each day because of poverty-related causes? I honestly do not have a simple answer. But here I should mention that the class of the second group of students above was organised by a Christian community that works among the urban poor. The students were either involved in the community or interested in their work. They would have been exposed to the lives of the urban poor, although some of the students are middle-class Australians. They might not have sold all their possessions, but had spent time with the marginalised and disadvantaged. What encouraged me most was their ability to hear the voice of the girl in the cartoon who lived in poverty. Their concern was not whether it was wrong to be wealthy, but to let the voice of the poor be heard. Economically there was a gap between them and the poor. But their heart was to bridge that gap by listening to their stories and spending time with them.

To me, this is how we can start to understand the Scripture’s mandate to proclaim good news to the poor. We listen to the Scripture and seek to follow Jesus’ way of life. We spend time with the marginalised and hear their cry. We allow the Spirit to work in us so that we can be authentic followers of Jesus. For the Scripture is not about a set of abstract theology, but the story of a loving and faithful God acting in the world. And he invites us to partake in that divine drama by standing in solidarity with the poor. Let us faithfully accept his invitation to love him and serve the poor.

Siu Fung Wu works in the Global Education team at World Vision, and is a writer and sessional lecturer at several theological colleges in Melbourne.

Cartoon by Peter Nicholson from "The Australian" newspaper: www.nicholsoncartoons.com.au

[1] Bruce Longenecker, Remember the Poor (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2010), 295.

[2] Longenecker, Remember the Poor, 301-10.

[3] It seems to me that this is a clear indictment against the Pharisees in Luke 16:16, who knew the Scripture well but put money first in their lives.

STUDY QUESTIONS

1. The Wesleyan tradition has often talked about the 'quadrilateral' of Scripture, Tradition, Reason, and Experience when it comes to theology. In what ways might your personal experience or history open up parts of Scripture to you, or blind you to others?

2. Jesus said, "If you continue in my word, you will know the truth and the truth will make you free" (John 8:31-32). What is the relationship between discipleship and understanding?

3. How does the estimate "65% of Christians in the Pauline house churches lived at or below subsistence level, ... 25% at “stable near subsistence level” [and] 10% had moderate surplus" alter your view of the life of the early Christians and their responsibilities to one another?

4. What opportunities are there for you to enter into the world of the poor today, individually or as a church?

5. How does this reading of Scripture challenge your attitudes toward and use of money?